The SIERRA NEVADA MOUNTAIN RANGE/YOSEMITE/CALIFORNIA/UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Chapter 1

Celestials on the Rails

(excerpt from the sequel and as yet untitled)

|

By the time Li Chao arrived in the land of plenty, many of his fellow countrymen had

. . . WHAT WAS HERE BEFORE, IS NOT HERE ANYMORE. The decision to remove the vast expanse of this opening chapter, I believe it has gone through some revisions since laid out earlier. (and . . . shhhhh . . . but I'm not so fond of the so few options there are to customize the style here, and I'm wondering if there's a way to put this out there, as in a word docx format, where others, anyone, can read it. I know there are ways, but how to publicize it here is an issue to check into . . . because this really looks dusty to me. Consequently, some content will remain, but it's going to take some time and a little courage to plunge into editing this site. The attention now should be about trying to complete a book by summer's end (what a horrible thought, summer's end--It's just beginning to feel like it here). The weather (good, bad, anything but snow for now), and a May deadline, consumed interest and time, so now it's time for a bit of cleanup and putzing in the yard. "If I were a rich man, all day long I'd biddy biddy bum, if I were . . ." PORTIONS OF PAGES MAY BEGIN TO DISAPPEAR HERE. (what does that mean?) Revisions and edits begin, and still no end in sight. So, please excuse but what's left here will become really choppy. Scan it maybe, but it's rough. (omitted) . . . Another class emerged. They joined a man named Charley Crocker, who, in conjunction with another man, Theodore Judah (the one they called Crazy Judah – the engineer, said to have a few shingles loose in his upper story), came up with an outlandish scheme. Their idea was to construct a railroad, mapped to run smack dab through the ageless, vaulting towers of the Sierra Mountains in California. Work would commence near the western base. |

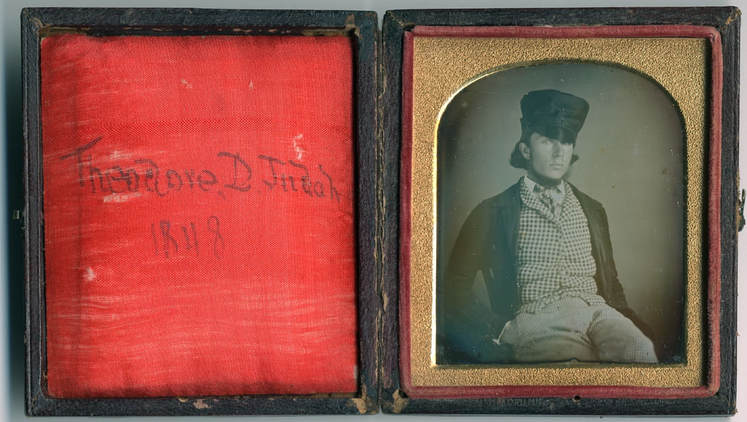

Theodore Judah, age 22, probably dreaming already? Photo by permission, courtesy of California State Library

omitted . . .

The Sierra Nevada mountain range, flanking California’s eastern boundary with Nevada, held ancient peoples long before a horse’s back gave their feet a lift, before the gift of snorting power; before white prophets came; longer still before the iron smoking horse, the modern kind that took to (OMIT --flag for rewrite in Word docx) tracking rails instead of trails. As majestic as they ever were, the Snowy Mountains stood in reclusive splendor . . . until the mid-1800s. Assertive human minds sought to refigure, make

(to be edited in the near future . . . sometime in June)

Word was, even thinking of cracking such rock was pure and utter craziness. Tunneling through was even greater madness. Nowhere but in a determined dreamer’s mind, a wild, white-mind, juiced with newfound faith in the prowess of technology, would a human ever conceive of boring its way through. Yet, these dreamers, schemers, did exist, so with the project ordained and provisions amply funded, the developers sought to enlist the labor that would drive the projected roadbeds over and through the impossible fortress known to be the High Sierras.

Desperate for cause, the promoters cast about for a class of people – anyone desperate enough, willing to work anywhere, in any kind of environment – for thirty, maybe forty dollars a month. Enter: Immigrants from the Orient – the Celestials. Smaller in stature, appearing physically less-endowed than other immigrant classes, they were hungry – and proved to be, beyond most any reasonable doubt – the right race for the job. Recruited on a trial basis, the Chinese passed muster with flying colors. Throngs more joined the original fifty. Before long, it seemed that the crazy idea might become a reality after all. Workers would actually risk their lives trying to blast and pick their way through some of the most rugged, mountainous terrain America had to offer. Though nothing was certain, hope made a bet that the oft-stymied overland wagons, the gruelingly hard conditions of horse-and-buggy travel would forever be gone, swooped away by a swell of steam from a transcontinental railroad.

This kind of work would test, molest, mangle and exterminate some of the best, but with every roadbed set, with every rail, spike and track, history began to take shape under the high command of manifest destiny, blessed, extolled, and promoted by California’s governor Stanford himself. The groundwork for a progressive new nation was under construction. Subdue the land for goodness’ sake.

Construction on the Central Pacific Railway began in 1865, originating in Sacramento, California. In an easterly direction, it tracked up the gentler slope of the Sierras before reaching its zenith in the snowy mountains. After piercing the mountain to create the

Summit Tunnel, the railroad would emerge to descend down its more treacherous, steeper, eastern slope, proceeding onward into the flat wastelands before it made a rendezvous with its counterpart, its other half, the Union Pacific, coming from the other direction. The two factions anticipated butting heads somewhere in Utah.

Somewhere within the upper regions of these mountains, where only mountain goats dared stand before, Li Chao found himself on the edge of a ledge. Four countrymen stood back, bracing themselves. In their hands they grasped a thick, braided rope that wound around their forearms and fastened securely to a boulder. The other end of the rope was tied to a sturdy woven-cage with a wooden platform, large enough to carry a man and a few tools. Li Chao, in the basket, rested on the precipice of a high cliff.

It all seemed like a dream. Standing inside the cage, he felt the quirky, jerky motions as it jostled off the side of the cliff, and there he was, like a dead man hung, dangling in mid-air. The men above shouted down to a figure they could no longer see. Li Chao answered, calling every so often to advise them of the progress as they lowered him, by degrees, along cliff’s wall. Finally, a good hundred yards from the top, having located the section of cliff that jutted out too far, the part of the rock that needed blasting before a timber could be inserted vertically to become a pillar for a bridge, Li Chao yelled out. In the timbre of a ten thousand hawks, he told his handlers on top stop his descent, hold him fast.

Suspended in a timeless surround, where only the wind could touch his thoughtful face, Li Chao sucked in the solitary experience as naturally as a practiced monk. Though he felt confident in his assessment of how things came to be, a haunting doubt continued to question what was real. If a dream, certainly an exciting one with gaps to fill, the most worrisome appeal that tossed around, seemed to demand an answer to . . . how did I get here? The usual sounds, the clanks of steel, the barks of men, could not traverse the distance over the ledge and down the cliff. The whishing sounds of wind gushed with a force that signaled change. Previously graced by a honeyed light in preceding days, the north face was changing its tune in a chilling chorus of approaching storms. Light snow began falling.

Li Chao let his eyes drift back and forth among the forests of faraway trees. Their crowns, like waves, swayed in a struggle with the gusting wind. His cage jerked. Jostled, maybe. It was high time to get on with the task. Picking up the two sticks of dynamite he’d fused together the night before, Li Chao felt along the length of its kerosene-soaked rope. Reaching to touch the cold Sierra cliff, he sought the elusive crack, the one just wide enough to accept his bundled bomb. Once found, he wedged in his ammo – then tucked it in, gently.

Letting out a loud, distinctive hoot, he signaled his readiness to light the fuse. The sound traveled up the lifeline, and though they could not see him, the men on top were quite sure that Li Chao was kneeling into position, preparing for a righteous outcome.

On his knees, budging a bit closer to the edge of the woven cage, he stuck his feet and legs through the larger weave at the bottom. Flexing his knees up to his chest, and then, by extending his feet to touch the cliff on its most extreme, puffed-out portion, he practiced the in-out pulse of his lower limbs, the drill that could save his life. Having convinced himself that the tack would work, he located suitable handholds on the basket. This would fortify his position and brace against the counter force produced by his leg-thrust.

Cursing the wind for the difficulty in lighting the match that would light the longer piece of pitch, once completed, with a somewhat shaky extension of his hand, he aimed for the crevice with the explosive package. The fuel-soaked rope of a fuse, animated perhaps by the bellowing winds, flamed surprisingly strong. Li Chao then fixed his eyes like flint. The sparking, sizzling glow coursed relentlessly toward its brighter, final destination. Counting seconds with incremental beats of his heart, he calculated the wick’s rate of progression before it would consume itself.

There was no need to watch any longer. The glow in the wick would not extinguish completely until a good chunk of the mountain went with it. The forecast suddenly became furiously clear. The wick was disappearing twice as fast as he first calculated! Seconds mattered. Grabbing the handholds, Chao placed his feet against the wall and prayed the propulsion would propel him in a faraway arc, enough to clear a jutting ridge above as the basket was being pulled up. If the timing was off, or the tug too weak, the pendulum swing would return the basket into a trap, an indented coffin of the granite wall. It was not easy to dismiss a fleeting thought that he’d never have another thought. He’d be bloody guts and bones; not a splinter to be found; nothing for someone to send home to his relatives to properly bury. Shrieking loud enough to reach the heavens, he gave the urgent command, “PULL NOW!”

(Anyone who would like to continue reading this chapter

can do so by making a request on the Contact page.)